Public companies, as we have noted, are required to report financial results quarterly. They do so by making public their Income Statements (P&L), their Balance Sheets which includes inventories, and their Cash Flow Statements. These statements are released quarterly and a company’s stock price is rises and falls based on performance against both budget and promises, called Guidance, the company made to Wall Street analysts. As a result, many businesses make extraordinary efforts to make revenue numbers at the end of these quarter periods. Customers have been trained over long periods of time to hold off purchasing until the end of the quarter because they know the company will provide greater incentives to purchase when their backs are against the wall to achieve their sales goals. Other than the operational stress put on the supply chain in these peak periods, there is financial stress applied to achieve or surpass inventory and absorption numbers to maintain the margins that were potentially compromised by the sales incentives.

As a result, inventories tend to be lowest at the end of the quarter. Companies can literally “drain the pond” of raw, packaging, and sub-assembly inventories to meet both the sales spike and the quarter end inventory number. The sales spike and drive to reduce inventory as much as possible are codependent. In companies with quarterly sales spikes, the draining of the inventory pond is even more pronounced.

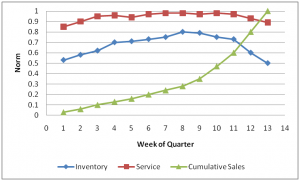

The graph below depicts the situation. Cumulative Sales is linear in the first two months of the quarter. The slope increases in the first few weeks of the third month and then increases again in the last two weeks. In this depiction, 40% of the sales occur in the last two weeks of the quarter. The inventory line shows the draining of the pond at the end of the quarter when sales spikes. The first two months of the quarter are spent building up the inventory to support the third month’s sales. While this example is a bit extreme, it is based on real company data.

There are many problems with this pattern.

- It is hard to forecast what will actually sell in the third month. A change in the expected mix could jeopardize achieving the inventory objective and could adversely impact customer service.

- In taxing both production and procurement, customer service is often compromised at the end of month and the beginning of the next simply because the pond may have been drained too much.

When we add customer service, line-fill specifically, for this case we see it has the same profile as the inventory curve.

There is one basic reason why this business profile exists: Companies are chasing sales pure and simple.

- Companies are chasing sales because they set aggressive sales goals. As the sales are not tracking as expected, management decides to offer incentives to drive sales in the last month.

- Once this profile is set, customers come to expect it. They know not to buy early in the quarter and they will get more favorably pricing and terms closer to the end fo the quarter.

- One and two feed off of each other, once engaged it is very hard to break this pattern much to the chagrin (and bear it) of the supply chain.

Does your company regularly "Drain the Inventory Pond?" If so, as a supply chain professional, what tactics do you use to meet this behavior head on? What tactics are you employing to try to change this behavior?